Is your company in the future going to be a producer of commodities or functional products or both?

Setting the stage

Functional products can be separated into B2B (Business-to-Business) and B2C (Business-to-Consumer) functional products. In the B2B competitive perspective, it is possible to establish a long-term collaborative relation with individual customers and even to produce customized products that suit large customers’ application needs (marked in red). In the chemical industry, such products are often referred to as specialty products, and customer services for and collaborative development of the customer’s use of such products is more in focus. In the B2C competitive perspective, apart from functionalities, branding plays a much more prominent role in consumers’ purchasing decisions (Lager & Blanco, 2010).

One classic example of repositioning along the value chain and a voluntary descent on the “functional ladder” is demonstrated by Dow Corning, where the decision was made to operate as a retailer of their more commodity-like products in addition to producing products with strong or medium product functionality. It was thus necessary to develop a better-adapted business model (and a new organizational subsidiary) that fostered a rather different culture, focusing on activities like cost-efficient supply chains and less on customer support.

Our perspective

As a consequence of different competitive dimensions on the market, commodities can be differentiated, into “upstream” and “downstream” commodities. Upstream commodities are defined in this context as primary raw material resources, like cultivated agricultural products, forest products, crude oil and so on. Products of this kind are often traded on raw material exchanges. Downstream commodities, on the other hand, are defined as upstream commodity products that are processed further, such as metals (copper, lead, zinc, etc.), structural steel, orange juice, aggregates, petrol, standard wood pulp, and so on. Such products are sometimes traded on raw material exchanges, but most often prices are set on the world market. Here one also finds commodity products that are marketed to consumers (B2C), like detergents, and food products like milk.

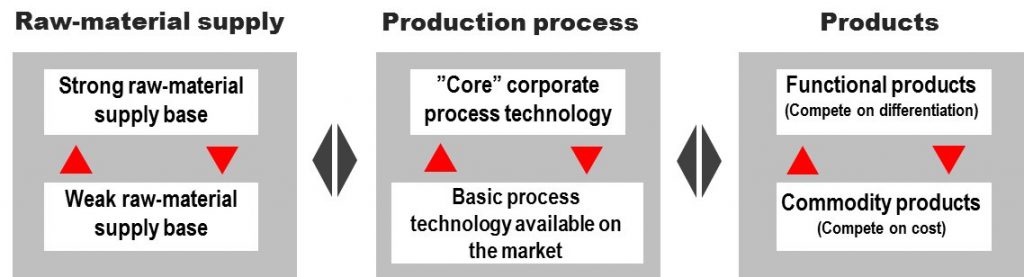

Raw material properties not only influence production costs and the complexity of appropriate production process technology but also often determine the quality and the performance of final products. Thus, securing a price-competitive and high-quality raw material supply base with a long-term perspective, as well as the development of such raw materials, should be prioritized highly by firms in the process industries. However, the ability to be a cost-competitive commodity producer, or a producer of more functional products, is also related to an ability to develop and introduce cost-efficient process technology in the production processes. Lacking sufficient resources for process innovation, corporate core process technology will inevitably be downgraded to basic technology.

When manufactured products with improved functional properties are introduced on the market, however, they are usually soon imitated as competitors try to produce the same type of product with the same performance; prices then gradually decline, and the functional products degenerate into commodities. A conceptual model of the downgrade – upgrade cycles for products, process technology and raw-material supply in the process industries. When proper innovation activities are lacking, all three areas will downgrade (Lager et al., 2013).